LLMs as approximate information synthesizers

Complex Systems and Computational Methods in Interdisciplinary Research

A simple -and short- framework for effectively integrating LLMs into academic and professional workflows

We all know by now that LLMs have been the most transformational tool that no one asked for—in the sense that there was never a clear use case or guidance when the technology was released to the general public. Since then, like many others, I have been exploring these tools, playing with them, reading about them, and trying to understand them. A few weeks ago, after I felt confident enough, I started sharing with my colleagues how I use "AI" in my work. These conversations motivated me to write this short post about the subject, as I believe I've found an effective way to explain how I integrate Large Language Models into my general workflow.

When a new tool is introduced, it comes with established terminology. In the case of Large Language Models, most people refer to them as "Artificial Intelligence," and this term has hyped the field so much that it's now used everywhere—as if adding the term immediately unlocks some kind of magical feature. The problem with this approach of using "magical," "esoteric," or "sensationalist" terms to explain scientific or mathematical concepts is that they aren't practical in the real world. So I'm going to use a different term to refer to Large Language Models (beyond just "LLMs") that can also help explain how I integrate them into my work.

LLMs are Synthesizers

Just as sound synthesizers transform elements of sound into useful and coherent outputs such as "music" through the lens of an artist, LLMs efficiently transform elements of information into useful information formats and shapes through the lens of a professional expert.

The analogy that has been extremely useful for me in finding good use-cases for Large Language Models in my workflow is to approach them as "Approximate Information Synthesizers." Just as sound synthesizers transform elements of sound into useful and coherent outputs such as music through the lens of an artist, LLMs efficiently transform elements of information into useful information formats and shapes through the lens of a professional expert.

Other way of looking at LLMs is as re-shaping machines that transform information objects from an initial state to a final one through their learned representations—the patterns capturing statistical dependencies between tokens. It is safe to imagine LLMs as re-shaping machines since that's a reasonable description to what they do to the data that its fed to them. And I will use the term "Synthesizers" because I think it describes better than "re-shaping" the process that goes inside the LLM.

These Information Synthesizers are "approximate" because of their stochastic nature. This means that whatever you want as output from the machine, it will return an approximation of that output. The quality of the approximated output varies depending on the difficulty for the synthesizer to build the exact shape that the user wants. This last point is one of the most complicated to address, since each LLM has its own learned representations, training dataset, and development methodology.

So when I think of Large Language Models and what they do, I usually imagine:

An abstract information object with specific shape properties that depend on the nature of the data representing or referring to the information

A universe of shapes encompassing all possible forms the information object can take

Paths connecting different shapes of the same information object

Going from a shape A to a shape B requires a transformation that can involve translation, reduction, or expansion of the original information object

The shapes of the information object are what the user can synthesize from the toolbox (LLM), and the amount and quality of information depends on the criteria of the user. Having said that, it is important to point out that we don't know the actual size of the universe of shapes that an LLM can create, since it depends on the specifics of the LLM (architecture, training data/method, representations learned, etc.).

Some examples of this process of going from shape A to shape B include:

Answering questions: The shape of the information is a question, and we want to transform it into its answer

Modifying a code function: This transformation requires a reduction or expansion of the original information object

Summarizing or elaborating a piece of text: A transformation that reduces or expands the original information object

Creating an image or video that fits a text: A format transformation/translation that reshapes the original format of the information (text) into a new one (image or sequence of images)

Some of these examples benefit most from adding contextual information (format examples, guides, documentation), as long as the length of your input + context remains within the context length of the Large Language Model. Sometimes, to get a better approximation, we need to create in-between shapes that can lead to the desired shape.

If the shape the user wants to create has a high error rate or is too far from the desired outcome, it means the LLM can't effectively synthesize that type of shape. In such cases, extra steps like fine-tuning or in-context examples (prompt design) might help narrow the gap between the current output and the desired result.

At the end of the day, we need to remember that these synthesizers are stochastic by nature, so we don't have full control over their functionality. However, we can steer them and enhance their utility through a well-designed AI-control framework that includes clear guidelines, feedback mechanisms, and evaluation metrics.

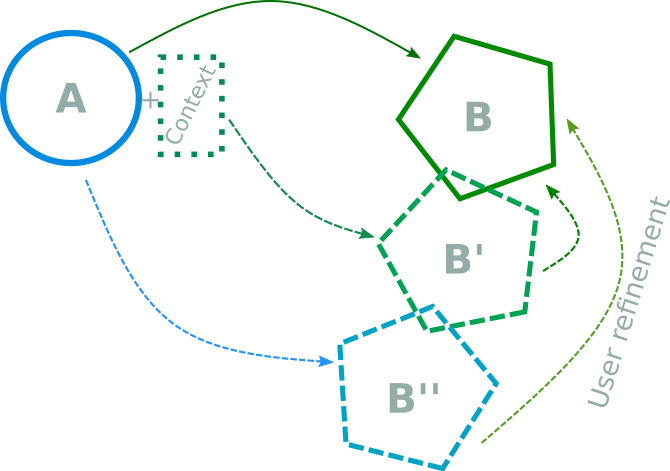

Framework diagram example. Using an LLM to go from shape A to shape B. When context is used the approximate output (B') that the LLM generates requires less work for the user to refine it compared with the path without context (B'').

Shapes can be found or created with the LLM's building blocks

The "building blocks" or learned representations of LLMs can be accessed indirectly by prompting the LLM. However, since there is no definitive guidance on how to use them effectively in specific use-case scenarios, this is something that the user will need to discover on their own. This makes the process less independent (not fully automated) but more accurate and safer through AI-control and Human-AI collaboration.

Here is the workflow I have been using with this framework:

Define a starting and an ending shape

Think of an activity you need to do and identify starting points

Define both shapes as detailed as possible; if something is difficult to define, imagine that shape and write down its detailed features

Define sufficient intermediate shapes that you know how to build on your own (without an LLM)

These shapes don't need to be as detailed, since they won't be the final output

Document each step thoroughly so the process can be semi-reproducible

Use the LLM to synthesize intermediate shapes and guide it to the final one

Depending on the nature of the shapes, additional user modifications may be needed between steps

This framework can be implemented in different ways, depending on the shapes you are working with. You can perform iterations with the LLM for refinement, or edit the shapes yourself to better fit your implementation.

An example of a workflow using this framework. LLMs can be used to create different in-between steps of approximate shapes, with refinement by the user if needed, in an iterative fashion before getting the final desired shape.

Use-case examples in my work

My work is interdisciplinary and requires extensive data processing and management, experimental design, hypothesis testing, and other scientific methods in my research and teaching. Integrating LLMs in my workflow has been extremely useful to:

Create simple images or mermaid diagrams for classroom presentations

Write code as an auto-complete assistant

Edit my writing for clarity (I do this at sentence or short paragraph level, as other approaches are not useful for me)

Create LaTeX/JSON/Markdown templates for my research and personal notes

Specific examples include:

Modifying plotting functions: LLMs excel at modifying long or complicated plotting functions quickly. This is a simple synthesis that requires the source code and either a specific example of what you want or details of what you wish to modify.

Creating new functions for code. Whenever I want to integrate code in my work, I:

Create a first shape that outlines the steps for the task the code needs to perform

Synthesize a second shape that includes an algorithm following the steps of the first shape

Synthesize a third shape containing pseudo-code that implements the synthesized algorithm

Synthesize a final approximate shape containing the code in my preferred programming language

This framework and workflow is transferable to other disciplines and allows users to maintain more control over the process. It enables them to incorporate their own expertise, adding that "human" perspective that brings genuine value to the final product.